How did Britain change so drastically from a nation obsessed with death and funeral etiquette to one – until recently – so averse to any mention of the topic?

Firstly, Queen Victoria died, in 1901.

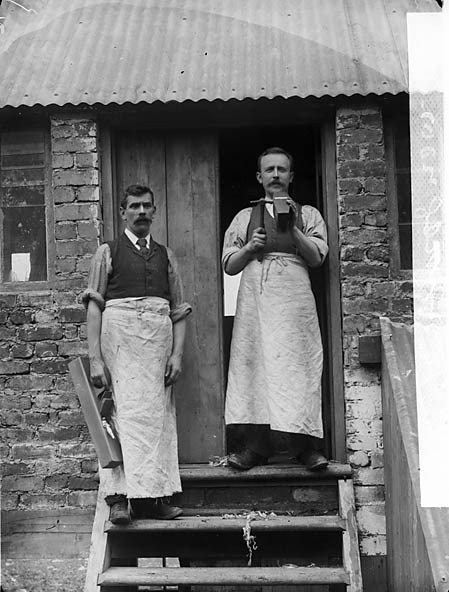

Then came the War; thousands of young men swept in great waves of patriotism and marched out through the village streets from their bakeries, mills, joineries, timber yards, farms, forges and families: to be swallowed by the hungry mud in Normandy.

The government needed to take a new view of how to manage the morale of the nation; their concern was that with so many dead, the nation could be overwhelmed by a griefstorm – which would weaken the resolve of the families who were required to instil duty in their menfolk, and wave enthusiastically as their sweethearts, their sons, their brothers and their fathers strode off to the front.

So, from Easter 1916, the grandest and then the humblest pulpits in the land, and the pages of every popular fashion magazine, people were urged to ‘cease this unseemly obsession with death’; and to ‘stop parading bereavement’; society magazines called ‘for mourning dress to be abandoned for soldiers killed in action’.

Grief, and death, began to become something to be endured in private, and mourning to take on a hidden – even shameful – nature.

Death began to be an unspoken topic. Death rituals became abbreviated, and people began to be distanced from those who died – only partly because bodies could not be recovered or sent back; for the first time children began to be excluded from funerals and death.

In exchange, we kept the black arm-band, the poppy, and the two-minute silence. Not to mention the ‘stiff upper lip’. And we handed over our understanding of death and our funeral traditions to ‘the funeral professionals’…………… known until then as ‘The Dismal Trade’.

Next blog post: The Changing Face of ‘The Dismal Trade’